|

Issue of January 11, 2007 |

|

|

Issue of January 11, 2007 |

|

|

Readme: Well, there you go. You put the clothes in the dryer, take the dogs for a walk, and suddenly it's 2007. Sorry about the irregular updates lately, but look on the bright side: subscribers don't have that problem. Yes, that's my bright side, but it could be yours, too. Anyway, somebody needs to tell Al Gore to knock it off. We get it. The grass is growing in January. 'Nuff said. I'm sure The Decider is working on it. This month marks the one-year anniversary of my abandoning Windows XP completely and permanently in favor of Linux. All I can say is that wild horses on rollerskates couldn't make me go back. I love it. As readers of my blog are aware, I still keep up on Windows-related news (schadenfreude, while not attractive, is loads of fun), and the new Vista OS seems to have all the hallmarks of a very unpleasant trainwreck. I cannot really recommend Linux to the average home PC user; it is perhaps 85% ready for that particular primetime. But I do have the solution for Windows users' frustrations with spyware, viruses and the myriad other annoyances of the Microsoft world: buy a Mac. Seriously. I have known several people who switched to Macs from Windows, and I have never met one who would ever consider going back. As for my medical adventures, it's been a heckuva year, Brownie. Unfortunately, what with getting irradiated every month or so and poked with large needles on most days ending in "y," my income has dropped precipitously, so if you've always meant to subscribe, time has come today, as they say. UPDATE: As a special New Year's bonus, I'm trying a little experiment. All of this month's columns (sans pictures) are also posted at The Word Detective Annex, a WordPress blog I have set up as a place for readers to leave comments on the columns. There is some sort of registration required to slow down the spammers, but it's not onerous. The theme I picked makes the whole place look a bit like a BP station. My hope is that, if folks stare at the throbbing whatsis in the upper left corner long enough, they'll send me pots of money. Next month I'll try to post links from each column here directly to its equivalent at the blog, but for the time being, if you have something to say, just pop over there, scroll down, and let fly. And, of course, the circus rolls on at da other blog. And now, on with the show:

Dear Word Detective: I came across this expression while reading

Treasure Island, and I thought I'd try asking you about it, even though

it's probably old-fashioned. It's used in Chapters 6 and 8. Page

references below are in the Oxford Classics edition. "I'll go with you

[in search of treasure]; and, I'll go bail for it, so will Jim, and be a

credit to the undertaking" (34). "...I would have gone bail for the

innocence of Long John Silver" (45). I think it means something like

"Bail" is quite a word. We "bail" our friends out of jail, the government "bails out" the airlines and automakers every few years, people "bail out" of airplanes or bad relationships, and we "bail" the water out of a leaky boat as fast as we can. As a noun, "bail" also means a cross-bar, especially the one forming the top of a wicket in the game of cricket, as well as being an archaic term for the wall of a fortress or the like. Several of these senses are definitely related, and some authorities believe they all are. The root underlying several senses of "bail" is the Latin "bajulare," meaning "to carry" or "to bear a burden," which begat the French "baillier," meaning "to take charge of" or "hand over or deliver." This "take charge of" sense produced the most common sense of "bail," that of "release of a person who would otherwise be in jail" either upon payment of a security deposit (also known as "bail") or into the charge of one who swears to ensure the accused's appearance at trial. This use of "to bail" meaning "to vouch for" or "to guarantee" produced, in the 16th century, the senses in the passages you cite, both of which amount to a solemn commitment to see the task through. The "bailing" one does on a sinking boat comes directly from the French "baille," meaning "bucket," but that word may hark back to the "carry" sense of the Latin "bajulare" as well. "Bailing out" of an aircraft probably echoes the sense of bailing water from a boat (although in the UK it is often spelled "bale," as if a bundle of something were being jettisoned).

Dear Word Detective: I am trying to find out the origin of the word "gnu." It is an alternate name for the wildebeest, a large African antelope. -- Jason. That thing is an antelope? Looks to me like a buffalo that's been through the rinse cycle once too often. But your email address indicates that you're writing from Zambia, so I'll take your word for it.

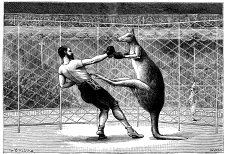

Onward. As you note, the gnu is otherwise known as the "wildebeest," which is Dutch for "wild animal," the Dutch having been a powerful colonial presence in Southern Africa at one point. "Gnu" itself is the word for the animal in the language of the Khoikhoi ethnic group of southwestern Africa. Early European settlers called these folks "Hottentots," a name, now considered offensive, which in the settlers' Dutch dialect meant "stutterer," a reference to the Khoikhoi use of "clicks" as consonants. The word "gnu" is presumed to be echoic in origin, an imitation of the snorting grunt of the animal itself. Although in Khoikhoi the "g" of "gnu" is pronounced ("g-noo"), in English it is generally not and the word is pronounced simply "noo." One notable exception, which has been running through my head since I started answering this question, is the immortal song "The Gnu" by the British comedy team of Michael Flanders and Donald Swann, who made a point of stressing the "g" right over the edge: "I'm a G-nu, I'm a G-nu, The g-nicest work of g-nature in the zoo; I'm a G-nu, How do you do, You really ought to k-now w-ho's w-ho's; I'm a G-nu, Spelt G-N-U, I'm g-not a Camel or a Kangaroo; So let me introduce, I'm g-neither man nor moose, Oh g-no g-no g-no, I'm a G-nu." p.s. -- There is also a free, open-source computer operating system called GNU, commonly encountered as part of the GNU/Linux operating system.

Dear Word Detective: What is the origin of the word "kitty" when used to mean a "collection of cash between several people"? -- Alan West. Good question. I'm more familiar with the plural form, "kitties," which are small hairy creatures that collect cash from your pocket in return for shredding your furniture and sleeping in the sink.

Since I mentioned cats, the first step in our kitty-quest is to note that "kitty" in the "money" sense has no connection to "kitty" in the cat sense, a form of "kitten," which in turn is derived from the French "chaton," the diminutive of "chat" (cat). And although, as fans of "Gunsmoke" will remember, Miss Kitty was often seen hovering in the vicinity of poker games in the saloon, her moniker was simply a derivative (along with "Kate" and "Katy") of the name "Katherine," and thus unrelated to either gambling or cats. Now as to the origin of "kitty" in the "collected money" sense, which first appeared in the late 19th century, the Oxford English Dictionary has an interesting theory, tracing it to "kidcote," a dialect term from northern England for a prison. The OED is silent on the exact logic of this "kitty-kidcote" connection, but Michael Quinion (at the excellent www.worldwidewords.org) notes a related theory that the money in a gambling "kitty" is "locked up" for the duration of the game as if it were in prison. Mr. Quinion rates this theory as not credible, and I agree. Far more likely is a connection between "kitty" and "kit," an 18th century English slang term for "outfit" or "collection," also found in a soldier's "kit bag" and "kit and caboodle" meaning "a collection of everything."

Hey fella, looking for a swim upstream?  Dear Word Detective: I've just discovered how hard it is to do your job. I know that the phrase "mack daddy" came originally from the word "mack," meaning "pimp," and that "mack" was short for "mackerel," the fish. I also know that the word "mackerel" has been slang for "pimp" in other languages for a long time (e.g., French "maquereau"), but how did this rather innocuous-looking fish come to be associated with procurement and how did the word get into the English language? -- Jackie. Well, it wasn't that hard until you came up with this question. This one gives me a headache. "Mack daddy" is US slang, primarily in African-American use, currently used to mean a successful, influential and stylish man, especially one popular with women. It is true that "mack daddy" was formerly (and sometimes still is) understood to mean a prosperous pimp or other criminal. But usage has shifted over the past decade or so, and "mack daddy" (or "mac daddy") is now often used as a more positive and generalized term, as in this citation from Ebony magazine in 1999: "[Comedian Chris] Rock ... remembers ... staying up late on school nights to watch the Tonight Show. 'Especially when Bill Cosby used to host ...,' Rock says. 'He was like so cool. He was a Mac Daddy back then.'" The phrase "mack daddy" itself seems to date to the early 1950s, when an anonymously-composed song called "The Great MacDaddy" became popular in the African-American community. The element "daddy" is fairly straightforward, having originally been slang for "pimp" that later, like "mack daddy" itself, broadened into a more general term for a man with a commanding presence. The "mack," however, is where the headache comes in. It does appear to be short for "mackerel," but the root of "mackerel" itself is in some dispute. And some fairly weird dispute at that. The standard theory suggests that the root of "mackerel" in French reflects an old Germanic word for "broker" or "pimp" because it was believed that the mackerel fish either has some odd reproductive habits itself or (I swear I am not making this up) assisted somehow in the reproductive antics of herring. In any case, the French have been using their equivalent of "mackerel" to mean both the fish and a pimp for several centuries, and "mackerel," which appeared in the "fish" sense in English in the 14th century, has also been used in the "procurer" sense in English since sometime in the 15th century.

Dear Word Detective: I was doing a crossword puzzle recently, and to my surprise the four-letter word for the clue "Works hard" turned out to be "moil," a word that I was not familiar with. When I looked it up, this was one of the definitions listed (the other was "turmoil"). Apparently the origin of the word was the old French "moillier," "moisten, paddle in mud," from Latin "mollire," "soften." Do you have any idea how this word came to mean "hard work" in our muddled language? I realize that paddling in mud is not an easy task, but wonder if there was also some confusion with the similar word "toil." -- Michael Hooning, Seattle, Washington. Indeed. Had I been doing that puzzle, I'd have been stumped as well, which is one reason why I gave up crosswords years ago. Even on those rare occasions when I emerged from one not feeling like an idiot, I always wondered why there wasn't some sort of prize for finishing the thing. A free lottery ticket. A cupcake. Something. In a perfectly logical language, "moil" would be related to "turmoil," and probably to "toil" as well. After all, they rhyme, right? And "turmoil" actually has "moil" smack dab inside it. That should count for something. Unfortunately, English apparently didn't get the memo, and all three words have their own unique origins. "Turmoil," meaning "a state of disturbance, commotion or agitation," has a murky past, but the leading theory traces it to the French "trémie de moulin," which is the hopper that holds the grain to be ground at a mill. Apparently the grain is stirred up in this process, making a plausible metaphor for any sort of disorder. "Toil," which first appeared in English in the 13th century with the meaning "to dispute or argue; to struggle," has a remarkably similar origin. Its ultimate root is the Latin "tudicula," a machine for crushing olives. From the original sense of a struggle between people, "toil" came to mean "struggle to make a living," and finally simply "to labor very hard." "Moil" does indeed come originally from the Latin "molliere," to soften, usually by moistening, also the root of "emollient." An early meaning of "moil," in the 16th century was "to make oneself wet and muddy," presumably in the course of menial and unpleasant labor, the equivalent of "getting your hands dirty" today. The sense of "moil" meaning "turmoil or distress" apparently arose by a confused association with "turmoil" in the 16th century. In fact, the cross-pollination between the two unrelated words worked both ways. A sense of "turmoil" appeared about the same time with the meaning "to toil or drudge," i.e., "to moil."

Dear Word Detective: Can you say what "snollygoster" and "snurge" mean? -- David. Sure, no problem. A "snollygoster" is a person, most especially a politician, who is motivated in all things by personal ambition and greed rather than admirable principles of duty and self-sacrifice. Regarding politicians, that description is, of course, largely redundant, but while most politicians may be "snollygosters," not all "snollygosters" are politicians. Many of them sell things on eBay, for instance. A "snurge" is a despicable person, especially a sneaky little toady whose greatest joy comes from ratting out other people to the teacher, boss or other authority figure in order to curry favor with those in power. It seems reasonable to assume that (if they survive their childhoods) many "snurges" grow up to be "snollygosters."

The most likely origin of "snollygoster" is another, very similar, word -- "snallygaster." From the German "schnelle (quick)" plus "geister (spirits)," a "snallygaster" was a mythical monster (a giant reptilian bird, according to one source) said, among residents of Maryland, to attack and eat livestock as well as the occasional child. Just how Maryland's version of Rodan came to be associated with avaricious politicians is anyone's guess, but the resemblance of "snollygoster" to "snallygaster" is too striking to ignore. There is a slight dating problem with this theory, in that "snallygaster" has (according to the OED) first been found in print in 1940 (versus 1846 for its presumptive descendant "snollygoster"), but it's entirely plausible that the "snallygaster" had been used to cow disobedient children for at least 100 years before the word made it into print. The origin of "snurge," unfortunately, is more of a mystery. Perhaps influenced by "sneak," it may well be onomatopoeic or "echoic," invented as an unpleasant little word for a unpleasant little person. According to the eminent etymologist Eric Partridge, "snurge" dates to the 1920s and originally was used in England as slang for a workhouse for the poor, eventually becoming students' and armed services slang for a "twerp."

|

All contents Copyright © 2006 by Evan Morris.